|

Sam Phillips Recording Service

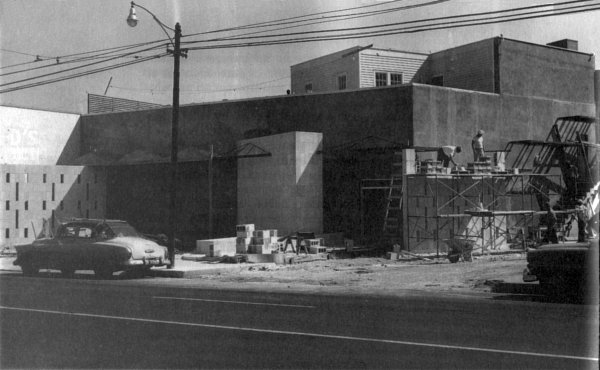

In July of 1958 Sam Phillips bought a property at 639 Madison Avenue just blocks from the studio at 706 Union Ave. By this time he felt the studio was creeping into obsolescence and too small to accommodate the increasingly large groups they were recording. The control room was too small to install the crucial new multi-track recorders and the office area was too cramped to house even his skeleton staff. He also wanted to diversify into custom recording (hiring out studio time), and developing Phillips International into an album label with diverse brands of music. He had started it 1957 because he felt Sun was too closely identified with rock 'n roll.1

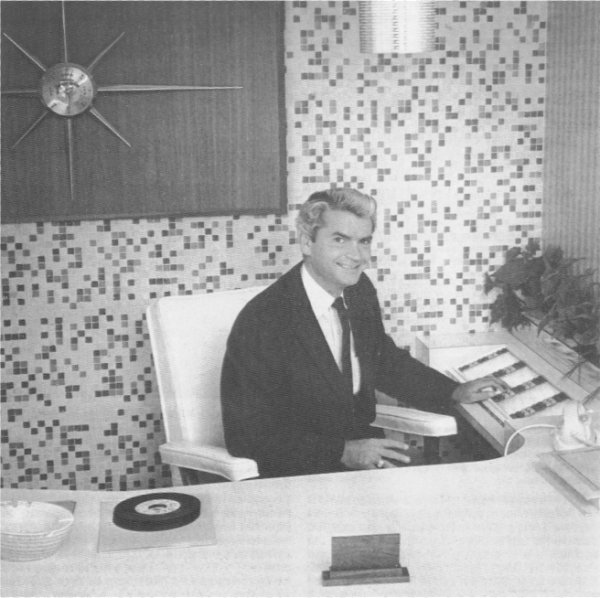

The building at 639 Madison had previously housed a Midas Muffler shop and also a Bakery. The interior was gutted and two modern recording studios were installed on the ground floor.1 "Sam was very much involved in every detail of the design of this studio. He put a lot of thought into it," says studio manager and chief engineer Roland Janes.2 The second floor housed the A&R and promotion offices and a vault set aside a vault for tape storage. Sam finally built an office for himself on the third floor, adjacent to the accounting and publishing offices, complete with jukebox and nearby wet bar. The space age motif, by Decor by Denise, according to Colin Escott, took on the look of a late `50s Buick.1

The studio was designed to be a stereo facility with a custom-made console, and it had an Ampex 3-track recorder. There were also three live echo chambers. The tracking space had an isolation booth and stair-stepped risers that were designed for setting up guitar amps. It had been in use off and on as early as January of 1960 but was officially was launched on September 17.1

Adding to his staff, Scotty had been brought over from Fernwood Records in June of 1960 and named studio manager and chief cutting engineer. Charles Underwood, composer of "Ubangi Stomp," and who also happened to have made the leather guitar cover for Elvis' Gibson, was hired as A&R manager and assistant engineer. They essentially replaced Bill Justis and Jack Clement when they left. Bill Fitzgerald had taken on the ill-defined role of general manager at Sun and Cecil Scaife, became manager of promotions.1

According to Colin Escott, the difficulties began to mount even before the tapes started rolling. The studio architect was drafted, leaving others to pick up the pieces. "We had problems from day one," says Cecil Scaife. "For a start, the roof leaked because of all the flat surfaces. Every time it rained I'd have to go over there with buckets and mops. It delayed the opening for six months."1

That was nothing compared to the real problem with the building—untamed acoustics. "The room wasn‘t tuned properly," asserts Scaife. “The sound was too hot. Too alive." Sam's instincts as an audio engineer, which had served him so well at the old studio, deserted him on Madison Avenue. The tightly focused slapback echo at the old studio had been replaced by a cavernous hollow sound, as the audio signals leaped around the huge floor and off the corrugated ceiling.1 To solve that, Sam ordered custom-built reversible acoustical wall panels that are reflective on one side, absorptive on the other.2 However, they turned out to be more decorative than functional.1

When Steve Cropper, along with Booker T and the MGs recorded Green Onions, Scotty was one of the first to hear it. Steve brought it there the day after they recorded it to dub a copy, since Sam's was the newest studio in town with the latest state of the art equipment. They had both mono and stereo mastering rooms and Scotty did work like that for just about everyone in the area. The only other place to go at the time would've been Nashville.3

With the successes of bands like Steve's and Bill Black's Combo, Scotty brought Stan Kesler, who was an engineer there at the studio and several musicians into the studio on a Sunday morning to record some instrumentals. Sam came in and even though Scotty paid for the studio apparently was displeased. The following March in Nashville, Billy Sherrill produced an instrumental album for him, The Guitar That Changed The World, on Epic. After telling Sam who he thought might be pleased, he was later given a letter suggesting he seek employment elsewhere. He relocated to Nashville.3

Sam, however, had many things going on and his interest in recording was waning, as a result, his new label according to Escott, suffered from his lack of deep commitment and eventually folded in 1963. Escott also said its doubtful that Sam ever truly learned to love the new technology. The complex was everything that 706 Union was not: spacious, state-of-the-art, and soulless.1

"It was awful hard to create there," recalls Scaife. "706 Union had a terrific atmosphere. A creative atmosphere. There was a naturalness about it. You felt up when you walked in. The new studio had a sterile atmosphere—it was like a doctor's office." Inevitably, the result was the loss of the classic Sun Sound. Sam's various managers and producers made random stabs at a bewildering variety of musical styles; consequently, his own personal stamp faded from the Sun catalog.1 In 1969 Sam sold the Sun Records label, and its catalog to Shelby Singleton. His sons, Knox and Jerry have run the studio and a music publishing company in Nashville. Sam focused on the radio stations he owned in Alabama until his death on July 30, 2003.

Over the years however, classic hits were recorded at Phillips, including the Amazing Rhythm Aces' Third Rate Romance, Jerry Jeff Walker's Mr. Bojangles, Sam the Sham & The Pharoahs' Wooly Bully, as well as John Prine's album Pink Cadillac and The Yardbirds' Train Kept A Rollin' and "Mister, You're a Better Man Than I." 2

The studio is still an analog facility with a Studer A80 multi-track and a DDA 36-in/24-out console. Roland Janes, the guitarist on many of the Sun classics, went to work there in 1982 said the studio was totally retooled around 1995. Laboring whether to take the studio digital or not they finally determined to stay analog. Today, both Phillips and Sun are active studios, and artists come from all over the world to experience some of the historic magic.2

page

completed and added May 31, 2013 See also the 1959 Press-Scimitar article Story of Sam Phillips, Memphis Recording Pioneer 1

according to or excerpt from Good

Rockin' Tonight by Colin Escott

|

|

All photos on this site (that we didn't borrow) unless otherwise indicated are the property of either Scotty Moore or James V. Roy and unauthorized use or reproduction is prohibited. |