|

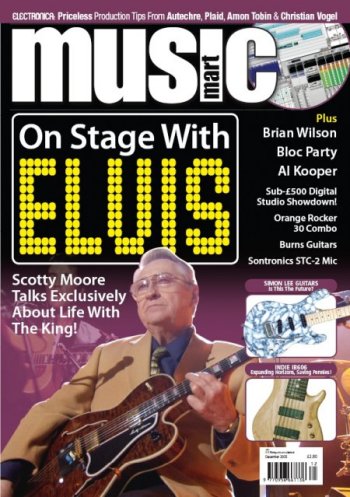

The Guitar Man

by Jonathan Wingate Elvis’s guitarist, Scotty Moore talks to Jonathan Wingate about the summer night in 1954 when a black and white world turned technicolour and rock and roll was born Scotty Moore was 22-years-old when he first got together with bassist, Bill Black and the then unknown 19-year-old singer on 5th July 1954 at Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios in Memphis, Tennessee for an audition that would not only change his life, but change the way the world looked, felt and sounded. “When I heard it,” Keith Richards said of Moore’s playing on Heartbreak Hotel, “I knew that was what I wanted to do in life. Everyone else wanted to be Elvis. I wanted to be Scotty.” Two weeks after the audition, That’s All Right (Mama) was released on Phillips’ Sun imprint. It was the start of Scotty Moore’s 14-year relationship with Presley as his first manager, chief guitarist and one of his closest friends. Over that time, they recorded more than 300 songs together. Presley had never made a professional appearance, and had actually only met Moore and Black for the first time less than 24-hours before his audition. Do you remember your first guitar? “I think the first one I really remember was a Gibson jumbo. I started playing when I was 8 or 10 years old. I stayed out of school one year when I was about 14 because I was just tired of it. My dad gave me an acre of cotton, so I sold it to buy the guitar.” Did you really start to get to grips with the guitar during your year off school? “During that year, I started working harder on the guitar, then I went back to school and stayed about a year and a half before I joined the navy when I was 16. I stayed for four years, and then after I came out of the navy, I went back to Memphis. I started a band - Doug Poindexter and the Starlight Ramblers, and Bill Black was the bass player. “I came out of the navy and ended up getting this band together in Memphis. You just had to pick up guys from all around. That made it really rough, because you didn’t know what you’d end up with because it would be different guys every time. I didn’t like it at all. Our arrangement was that if I don’t have something for us to do for the weekend coming up by Wednesday of each week, you guys can do what you want.” How did you meet Sam Phillips? “ Well, I didn’t know he had a record label at the time, but I knew that you could go in and cut acetates. Once I realised he had a label, I went in there and got an audition. He asked us if we had any original material, but I’d never even thought about that. Writing songs and playing music were pretty much seen as separate things back then, because I don’t think anybody really thought about making money out of songwriting much. “I went home and Bill, Doug, my oldest brother and I put a couple of songs together. We went back to see Sam, and he cut his first record with us, which was called My Kind Of Carrying On. I don’t even think I ever tried to write anything after those first things, because I was too busy trying to play.” Were you working a day job at the time? “Yes, I was still working until mid afternoon, and then I’d drive by the studio a couple of times a week. If Sam wasn’t busy cutting demos for somebody, we’d go next door to Miss Taylor’s Restaurant and have coffee and just sit and talk about music and stuff. Then one day, his secretary Marion Keisker came over and had coffee with us, and she says: ‘Sam, did you ever talk to that boy who was in here a few weeks back? He had a real good voice.’ “A couple of weeks went by, and Sam still hadn’t called him, so he asked Marion to give his number to me. I looked at it and I said: ‘Elvis Presley? What kind of a name is that?’ I called his house that afternoon, and his mother answered and said that he was at a movie and that she’d have him call me. “He called me when he got home, and I told him I was working in conjunction with Sam Phillips of Sun Records and that we were looking for new artists, and then I asked him if he was interested. I didn’t realize this at the time, but in the back of my mind I was hoping to get some work in the studio from Sam with other artists. So I asked Elvis if he could come over to my house the next day, which was actually the 4th of July.” What do you remember about the first time you met Elvis? “I guess he came over around 1 o clock. Bill Black lived a few doors down from me on the same street, and I told my wife to get him and ask him to come down later. I just said: ‘Play what you feel.’ He was singing all different kinds of songs, and a lot of them he didn’t even know all the chords to, so he’d just keep playing and singing. The thing that impressed me most at that point was his timing. He could stop playing and still sing the whole song, and still the meter would be perfect and he’d be right back in time and then start playing again. “We spent a couple of hours just doing that, and when Bill came in, he didn’t play. He just sat around and listened to us for a little while, and then he left. I told Elvis I’d talk to Sam and that we might be in touch. When Bill saw Elvis’ car leave, he came back down and we talked for a few minutes. He said: ‘Well, he’s got a good voice, but it didn’t really knock me out.’” What happened next? “Sam said he’d call him and ask if he could come in to the studio the following night. He said: ‘I don’t want the whole band, I just want a little music behind him so we can see what he sounds like.’ So we went in on a Sunday night and went through the same thing. Sometimes Bill would bring up a song, sometimes it was me or Sam, but it seemed like he knew every song in the world. No matter whatever we suggested, Elvis could play it and sing some of it. It was country and blues, because that’s about all we was listening to really.” Is it true that this was actually an audition rather than a recording session? “It was absolutely the audition. I don’t know why people think it was a session. They think Elvis just came out of a magic pond. Anyway, it was just the three of us playing. We’d just do a verse and a chorus of something, and Elvis would sing along. I didn’t know half the songs myself, so I just faked along behind him a little bit to make us a little noise. “When we were doing regular sessions later on, we went through everything the same way, just kept going through songs, with Elvis singing a little of them, and Sam didn’t keep any of those, but he did keep a few of those very early things. When Sam sold his contract to RCA, a couple of those first things showed up, and I was crazy every time I heard them, because they were just strictly an audition.” How would you describe the atmosphere in the studio for that audition? “Oh, it was just friendly, we was having a good time, really. There wasn’t any pressure. When you think about most auditions, you go in, half of the guys are looking at what you’re doing. We didn’t have any problems just joining in on whatever he was singing, and we did this for a couple of hours. In fact, Bill and I were actually just getting ready to go home, because we both had to work the next day. “The door to the control room was open, and Elvis stood up and started playing That’s All Right, just beating on a guitar and singing it. Bill was just getting ready to pack his bass away, and he started playing along with him. I listened to what key they were in, and I started playing along with them. Sam heard it through the door, and he came out of the control room and says: ‘What are you guys doing?’ We’re just doodling around, I said. ‘Hey, get back on the mic, do a little bit more of this - it sounds pretty good.’ We did it in three or four takes and they had it. And that was the first record. Did you realise something special had just taken place? “We all liked the song after we’d done it, and Sam said it was good, but he didn’t say anything about releasing a record. So we all went home, and although I didn’t know it, he transferred the tape to disc and took it down to Dewey Phillips at WHBQ. When Dewey heard it, he played this disc over and over through the whole show and all the kids just went crazy about it.” How quickly did things move from there? “The next day, Sam called me and said: ‘We’ve got to get you back in here.’ I couldn’t make it that night, so we went back out to cut a B-Side a couple of days later. Like I said, I was hoping to get some session work from Sam. We went through the same thing that night trying different things. Bill started whacking his bass on both sides with his hands and singing Blue Moon Of Kentucky, an old Bill Monroe song, which was originally in waltz time. Elvis knew the words and he started singing along up-tempo with Bill. That would’ve been the first actual session, although the original audition was used to make the first single.” How integral was Sam Phillips to the sound of those early records? “Oh, he was very important, because if you go way back and listen to those old records like Bing Crosby, the singer will be way out in front of the music, even if it’s a huge orchestra. Well, that was the first thing that hit me when Sam recorded Elvis, because there wasn’t a bunch of us, and he made Elvis’ voice like another instrument. He put the voice closer to the music, and that hadn’t really been done before, not to my knowledge.” Did you know what sort of sound Phillips was looking for? “No. Sam didn’t know what he was looking for, but he knew it when he heard it. I’m not sure he would say the same thing though. He knew he was looking for something, but he couldn’t explain it to you, so we just kept experimenting. There really weren’t any influences on the sound. We just did it, because we had no reference points.” How important was Phillips’ use of reverb on those early Elvis recordings? “Well, whatever came out was an accident, and Sam didn’t do that on the session while we was cutting it. I guess he was making another copy of those tapes, and you could get reverb playing the second one back into the first one a little bit, and that would give you a slapback. He did that by accident, and it came up and he liked the sound of it. That reverb sound had been used in movies, but not on records.” How did you set up in the studio in those days? “Oh, I just set up the amp with a little mic in front of it. The three of us were sat fairly close so that we could see each other real good. There wasn’t none of these isolation booths. We just plugged in and did it. I started off on a Fender, but we were always sitting down when we were playing then. When I came out of the navy and I started playing around town, I was standing up the whole time, and I couldn’t hold the darn thing. So when I saw the Gibson ES295 was gold coloured, I thought – Boy, I’ve got to have it.” Why did he leave Sun? “See, Elvis outgrew Sun, and Sam couldn’t handle him, and he knew it. That’s the reason Sam sold him, because if you think about it, Sam started with Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash, but he created his sound with Elvis. He had the sound, and so he finally had something that was his and he could sell. That’s when Sam let Elvis go, so he could take that money and work on other artists.” You also worked as Elvis’ first manager, didn’t you? “I was his manager for the first year, just so Sam could say: ‘He’s already got a manager, don’t bug him.’ Then Bob Neil became his second manager. Bob did an early morning radio show. Bob Neil was a real fine man, but the whole thing got out of his hands too. “Colonel Parker was an old carnival character, so he was a hustler. He did a lot of things that were good for Elvis, and he did a hell of a lot of things that were bad for him too. He was very controlling. He started working on Bob Neil right away, and of course, he was also working on Elvis’ mamma and daddy. I tell you what – Elvis’ mamma could see straight through him in a New York minute. Elvis didn’t listen, but when all this fame hits you when you’re 19, 20 years old, what are you gonna do? That’s what I would have done. In fact, I think Elvis held himself pretty well, taking everything into consideration.” When did you start to realise that Elvis was going to be a big star? “Well, Elvis didn’t get worldwide or all over the country until he did Heartbreak Hotel when he went to RCA and we did the first thing on television. That’s when he exploded all over.” What do you remember about those early days on the road? “Even in the early days before Heartbreak Hotel, we’d often play gigs that were maybe 400 miles apart. We’d finish up one thing one night and then have to jump in the car, and we’d barely make it to the next one the next night. So we never heard what the people thought about us. Every time we’d play somewhere, there would be somebody there that lived in another part of the country, so the word would get around real quick. It didn’t spread as fast then as it would today, because the media wasn’t as big as it is now.” During those first few years, were you performing or recording almost constantly? “Oh yes, but when Elvis hit the movies and he started getting these chicken-shit songs, for the most part, I just kinda lost interest. The songs had no meat to them, and they had to be songs that fitted the movies. I was still leader on the sessions for quite a while, and I’d play on some of the songs – the ones I liked – but it just wasn’t my thing anymore. I never fell out with Elvis over this. He’d always wanted to be in the movies, and they never did get to really use his talent as an actor, as far as I’m concerned, mainly because of all of the music he had to do. He could’ve had good songs in those movies, but they were mostly just bull crap, teenybopper songs.” How did Elvis actually go about picking the songs he was going to record once he’d signed with RCA? “RCA would bring in a stack of demos from all their different writers for every session. Elvis would have one pile where he’d just throw them away, and then he’d have one stack that he’d say were maybe records, which he’d then play a second time. He’d go through the whole set before we’d even hear them, so we’d go off for a coffee or something. I didn’t want to listen to all of them and get my mind cluttered. “Once he’d picked something, we’d go back and start learning it with him, and then start working on it. RCA never stopped to realise what they had a hold of. All they could see was the dollar signs. Nobody ever knows about what’s gonna be a hit, but by that point, just about anything he put out would sell.” Did you record everything live in the studio? “We’d sometimes record everything in a couple of takes, but not always. He might have overdubbed his voice towards the end, but when I was playing with Elvis, we always did things live. But he was harder on himself than he ever was with any of us. We recorded in the day and at night, but later on in his life, it started being mostly at night or late afternoon into the night. There was no drinking around the studio, and I never saw any drugs in the studio, not during my time. We might go out after the session around midnight and get stoned, but never during a recording session. I really think that’s a mistake a lot of musicians make. “Mystery Train was the last thing we recorded on Sun, and I’d just gotten a new Gibson and the Echosonic amplifier, which created the slapback that you could do with tape machines. Hound Dog we cut in New York. Gordon Stoker is playing piano on the session, because Shorty Long had to leave to work on some rehearsal for a stage show. The background on Hound Dog sounds like a bunch of guys sitting around, although it’s just three people. “Don't Be Cruel", I turned my E string down to a low D. I played the intro and then I played a chord at the end, but that was all I did on it. Same with All Shook Up – I just played a little rhythm type of thing on that. Jailhouse Rock – shoot – I don’t remember anything specific, but it was just a rip romping song. One thing you realise now is that the songs and the music and the excitement is still there in those records now.” Would you say you were Elvis’ main creative foil? “Well, yeah, I guess you could say that. In the very early days, me and Bill just tried to play what fitted the music and the song rather than just playing a bunch of notes. Of course, I guess it was put on me more than anybody else, because Bill was just playing rhythm. In terms of the sound, we had no reference points, that’s for sure. My reference was just the song really.” Would you say that less is more is your basic philosophy as a guitarist? “Yes. Less is definitely more. I know there are some guitar players that are just barn-burners, but that don’t impress me a bit, other than the fact that my hands won’t move like that. I always listened carefully. I wouldn’t want to get in the way of something else, especially the singer. If Elvis was doing anything, I didn’t want to do anything that would step on his toes, and then when he wanted me to take a guitar break, he’d be the same way. We fed off each other. I guess you could say that there was a kind of musical telepathy between us. The one thing I always appreciated about Elvis was that he never tried to tell anybody what to play.” Was the ’68 TV Special the last time you actually played with Elvis? “Yes, and that was the last time I saw him too. I’ll tell you something I’d like you to put in your magazine - when we did that, DJ Fontana and I went out and had dinner at Elvis’ house in Hollywood. He said he wanted to talk to us, and we were looking at each other like – What did we do? And we went in and he said: ‘When we’ve finished this movie, I want to do a tour of Europe. You guys want to go?’ And I said – hell, yeah, all you’ve got to do is give me a little notice so I can get somebody else in charge of the studio. Of course, Parker put a clamp on that real quick when he heard about it because he couldn’t leave the country.” What do you remember about the ’68 TV Special? Well, we just did two shows in the round – one in the afternoon and one at night. For the actual performance, I think they spliced between the two. The main thing I remember is that I’m the only person on stage who’s got an electric guitar there. Elvis told us to sit down, and so I didn’t put a strap on his guitar, and I didn’t have one on my guitar either, so it was hard to stand up and play. After he did the first couple of songs, the crowd started getting good, he started feeling good, so he stood up. That’s when he turned to me and said: ‘Let me have your guitar.’ He couldn’t hear his guitar, ‘cos it was an acoustic. I gave him my electric and took his acoustic and just kept playing. That show was a lot of fun, but Elvis was very nervous at the beginning. He hadn’t been in front of a crowd for so long…well, since he came out of the army. I’m sure half of America was watching the show that night. I wasn’t nervous, because to me, it was just another crowd. After we did the ’68 Special, as I said, he wanted to go to Europe, and that’s when he hooked up in Las Vegas. I didn’t want to go because they wouldn’t pay us. That’s why I didn’t carry on playing with Elvis. The Vegas thing was only gonna go on for two or three weeks. That’s when they got James Burton and all those other guys playing with him. We didn’t have a falling out, but that was the last time I saw him or spoke to him. Elvis was really just like a younger brother to me from day one. After I stopped seeing him, I really missed him so much.” It must make you feel very sad when you stop to think of what happened to him after you lost touch. “I think about him quite a bit. I guess the main thing I can tell you is that he wasn’t happy towards the end of his life. It was depressing for me. I think Colonel Parker hurt him. Like I was saying, when we had dinner that night, he told us he wanted to go over there and do a European tour. He knew that the fans were over there, ‘cos he’d been to Paris when he was in the army. He’d seen enough when he was over there to know that here was a whole new life for him. That’s the reason he went back on the road, because it was in his system, and he wanted to get out and do something for the people.” How would you like to be remembered? “Oh, I don’t know. I might be an innovator, but I really don’t consider myself to be a fantastic musician. I just did my own thing my own way, and it just happened to be a little different to anybody else.” A Tribute To The King by Scotty Moore & Friends – Live At Abbey Road Studios is out now on DVD through out now on Universal Music This interview, copyright of |